Share Charlotte Hermine Benard's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

IN LOVING MEMORY OF

Charlotte Hermine

Benard

August 16, 1924 – July 29, 2024

Obituary

Charlotte was born in 1924 as the second daughter to Klementine and Edmund Blaschke. Her first years were spent in idyllic Perchtoldsdorf, a wine-growing town outside of Vienna, Austria. Her parents had a restaurant, and outgoing little Charlotte thrived on the attention of the guests, who liked to buy her toys and treats.

By the end of her elementary school years, however, the Austrian economy was in a state of extreme disarray. Unemployment was high, people didn't have spare income for restaurant visits, her family lost their lease and were obliged to move to Vienna in search of other work. Her father and older sister succeeded only in finding occasional part time employment, and the family moved from one uncomfortable sublet to another as their circumstances became ever more dire. Charlotte's mainstay was her friendship with her classmate Ruth Rosenthal. But political and social turmoil were waiting in the wings.

Soon, there was mysterious talk on the streets about a charismatic leader in Germany who was already making life better for the Germans, and who would soon be returning Austria to the Germanic fold and bringing prosperity and stability. In later years, Charlotte would describe those days when, as a teenager, she and tens of thousands of Austrians gathered in the streets to await the arrival of this mysterious savior: Adolf Hitler. In the place of stability, far worse turmoil was to follow. Her friend Ruth, along with her family, read the writing on the wall and decamped to safer ground. The last message was a postcard, with no return address, letting Charlotte know that they were in Belgium, were safe and were enroute to America. Charlotte never stopped talking about Ruth, how inseparable they had been, and how she wished she could have found her after the war or at least known for sure that she had indeed escaped to a safe and happy life.

Briefly, the Austrian economy did improve. There was employment and there were public services, and the Blaschke family moved into a proper apartment of their own once more, in Vienna's 9th district. But the boom was artificial, and only too soon, the country was at war.

Charlotte was now a graduate of a business high school, employable as a court stenographer and later as administrative secretary to an insurance company. Her elderly father, a veteran of WWI, was drafted and, too old to fight, assigned the highly perilous task of accompanying munitions trains. The tide of war soon turned against Hitler's Germany, and the bombing of cities including Vienna commenced. Charlotte's big sister, Paula, had married and was living in Switzerland, so Charlotte and Klementine were left to navigate the war years alone, with many days and nights spent in the basement of their building whenever the air raid sirens went off - as they did with increasing frequency. Charlotte now worked for a company that manufactured industrial wiring - a business that exempted its female employees from having to work in munitions or other war-proximate factories.

She often told the story of the day that Vienna fell. The Russian army was first to reach the city. The agreement among the Allies had been that they would meet at the outskirts, and that no army would enter the city on its own - but the Russians chose to disregard that promise. The Austrian soldiers abandoned the city and fled, and civilians - including Charlotte - rushed to the garrisons in hopes of garnering some of the abandoned food stores. But when she got to the nearby Rossauer Kaserne, fights had broken out over the supplies and everyone was knee-deep in flour and rice from the resultant torn bags. Unwilling to be part of the rabble, she wandered upstairs and drifted through the abandoned dormitories, where the frantically departing soldiers had left behind letters, photos, individual boots and helmets, the detritus of panic. After some time she noticed that the shouting from below had ceased and things were eerily quiet. Nervously creeping downstairs, she reached the courtyard of the garrison just as Russian troops were coming in. Their commanding officer yelled at her in broken German that she should run - a stroke of luck that she still marveled at 8 decades later. She made it home, climbing over barricades erected as a last stand by the desperate civilians, ducking into doorways as bullets flew; she made it through the terrifying days of the Russian occupation, partly by hiding in the linens drawer under the bed when soldiers stormed through Vienna's apartment buildings in search of young women. When the Allies arrived, the city was divided into sectors and the 9th district had the good fortune of being assigned to the Americans.

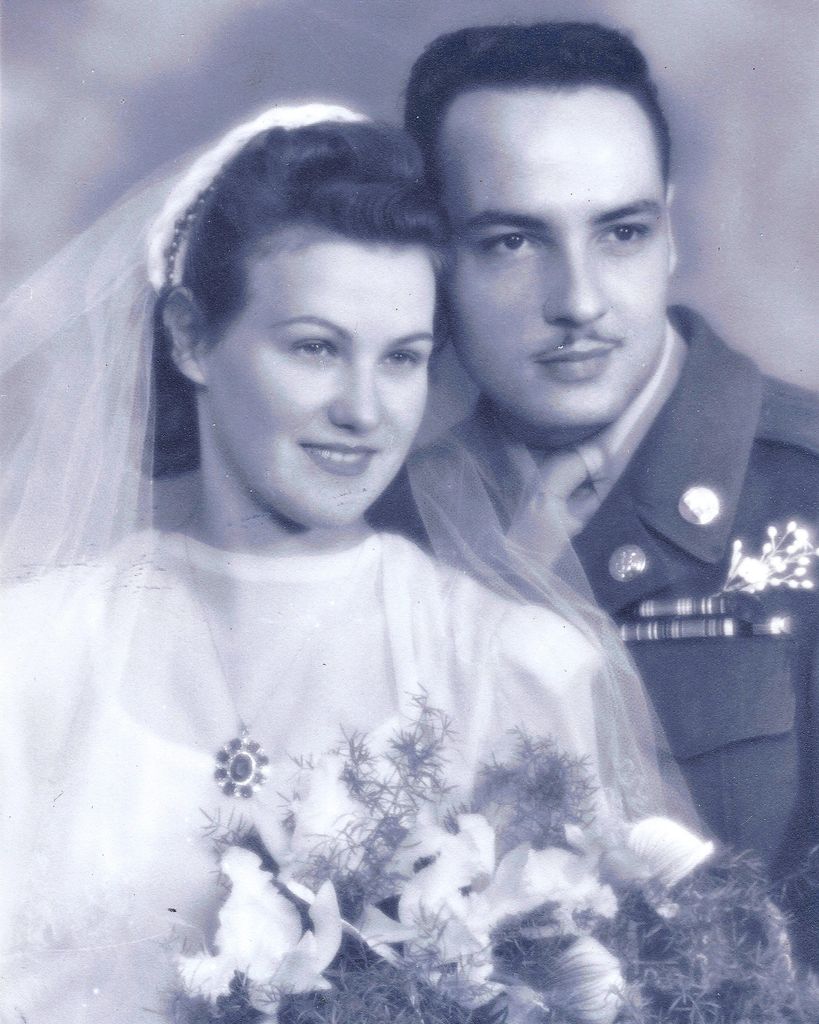

One of those Americans was Charles Benard, a young soldier from New Orleans who was in charge of logistics and acquisitions and who needed some industrial wiring. As the only person in the office with some level of English fluency, she was assigned to this task. Though when you think about it: Charlotte and Charles - there clearly was destiny in play and they were fated to meet.

Their wedding in the 9th district's historic Serviten Church was attended by the entire neighborhood, and decades later we would meet people who introduced themselves as her former flower girls. The handsome American GI and the pretty Viennese girl - it was quite the sensation.

The newlyweds lived in New Orleans for some years, until Charles - who stayed in the military after the war - was posted to Salzburg, then Augsburg, then Munich. The family - now with two children, daughter Cheryl and son Charles Etienne - lived in Germany, then in Albuquerque, New Mexico and Huntington Beach, California. After his retirement at the rank of Command Sergeant Major, Charles worked for a transportation company's overseas division and they again lived in Germany; Charlotte accompanied him on many business trips, to Lebanon, Iran, Egypt and more. After he retired, she felt the urge to resume her own career, and at age 65 she became the program manager to the McGeorge School of Law overseas program in Salzburg. She organized conferences in ski resorts, arranged internships and lawyer exchange programs, and coordinated lectures by US Supreme Court justices.

Charles suffered the challenging illness, Alzheimer’s, in his final years, and he and Charlotte lived with their son and his wife Elizabeth in Boston and Germantown MD. After his passing, McLean VA became their home.

Charlotte was a gifted storyteller and writer. She has left us, in book form, both her own life story and that of her mother Klementine, who grew up during the time of the Habsburg Empire, experienced both World Wars and lived to vote for Austria's membership in the European Union - quite a stretch of history.

Charles was the most generous, affectionate, open-minded and humorous parent, partner and friend anyone could hope for.

Charlotte will be reunited with him in Arlington Cemetery, where as a veteran of WWII, he was honored with a final resting place.

Both are sorely missed and most lovingly remembered by all whose lives they intersected.

Charlotte Hermine Benard's Guestbook

Visits: 70

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors